Author’s Note: This story features Darlene, the young widow of “Of War and Breakfast”, as an old woman who has lived out her life, dispensing wisdom accumulated from her own experiences and dealings with many people. Her origins start in another story titled, ‘A Journey Home.’ The idea to put several tales from her lecture to her nephew, who comes to visit one summer after many years, of those experiences she shares with him, came when someone suggested I take the experiences from her soliloquy and make them into separate stories. Miriam’s Camp is the third in the series. I hope you enjoy reading it. It is a tale of faith, so if you are not a believer, and wish to comment, please be respectful; I approve all comments prior to them being posted here.

Thank you, and thanks again for taking the time to read my story.

Alfred

She was never really able to answer why she got off the bus when she did, in front of the old house that lay on the bus route, a road of dust that seemed little traveled except for the people on it going somewhere else.

Every part of her ached from the old bus’s constant jarring, its suspension in dire need of repairs that would likely never happen; the only one it didn’t seem to bother was the driver, who was humming some tuneless song, if there was such a thing, over and over.

If there isn’t, he just invented it Miriam thought.

But she knew her focus was on the wrong stuff; his lack of tonality was not the issue, but a distraction from the truth of why she was coming back.

Get out of here, Miriam, they told her. See the world.

You’re young; you’ve got your whole life ahead of you to do whatever you want.

You’re a beautiful girl, Miriam. Good looks will take you places.

You could be a model.

You could be in movies.

It sounded glamorous, exciting and exotic.

It was actually wrong, crude, cold, and ultimately bloody; the ways of men and beasts, she discovered, were not dissimilar.

And now she was coming home.

******************

She needed time to think.

“I’ll get off here.”

The driver stopped humming.

“You’re a long way from where you belong, miss. That ticket’s only good for one ride.”

“There’s one I haven’t heard,” she muttered.

“Say, miss?”

“I’ll get out here.”

“You sure?”

“ Yes, I’m sure. Thank you.”

“Suit yourself.”

*******************

She stood there in a cloud of wheat colored dust that spun in little dervishes around her like a pulsing aura as the bus pulled off.

Stepping back out of it, she stood there as it settled on and around her, not quite sure what to do next.

“Best get out that sun girl, ‘fore you burn.”

The voice came from across the road; Miriam shielded her eyes from the sun with her hand and peered over.

An old woman sat in a rocking chair on her porch, a cup of coffee in her hand, and a thick book on her knees.

Miriam had never known anyone lived there. Of course not, idiot, this isn’t your side of town.

There were two rocking chairs on the porch. The other one was empty.

The old woman spoke again. “Girl, can you hear me?”

The woman was black; Miriam had never heard a black woman speak to her that way before. It was always, “Yes, Miss Whitcomb,” or “No, Miss Whitcomb,” or “As you please, Miss Whitcomb.”

“Child, come out that sun ‘fore you burn.”

Still somewhat dazed, Miriam found herself crossing the road.

The old woman didn’t stand up. Her brother would’ve called it an anomaly: it was his favorite word. Her father would’ve called it an affront, and dealt with it, but as Miriam got a closer look, probably not with this woman. There was a force to her, and undercurrent of vitality that didn’t seem to encourage or align with the nonsense of modern customs.

“Have a seat, girl. You look done in.”

Miriam looked at the seat, at the woman, at the book in the woman’s lap, and back at the woman’s face. It was old and lined, dark as oak.

“I’ve been sitting for a long time,” Miriam said. “I’ll just lean against this railing, that is, if it’s sound.”

The old woman looked at her then; she had kind and patient eyes that looked not at you, but through.

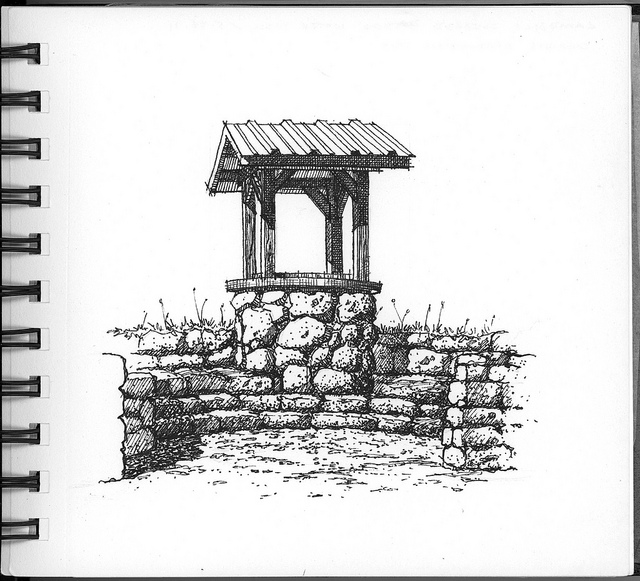

“My father David, God rest his soul, built this porch with his own two hands. Wasn’t nuthin’ out here before but that dusty road. If it ain’t sound, ain’t ‘cuz he didn’t build it right. Time, termites, and carpenter bees mighta done their share, but you’re welcome to stand, if you choose.”

The railing held.

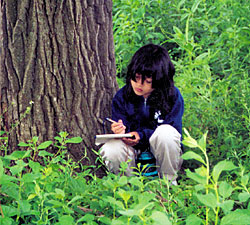

The old woman went back to her reading, her chair creaking, her finger on the page, tracking the text within.

Miriam watched a hawk circle over a distant field, but the silence pressed.

“Aren’t you going to ask me why I’m here?”

The old woman didn’t look up, kept tracking the words with her finger.

“You here ‘cause I told you to get out of that heat.”

“No, I didn’t mean that, I mean, here.”

“Figured if you wanted me to know, you’d tell me.”

“But you haven’t even asked me my name.”

“Figured if you wanted me to know…”

The girl smiled at that. “It’s Miriam.”

Darlene looked up.

“Well, Miriam, welcome to my home. I’m Darlene. Miss Darlene to you.”

Miriam tossed her hair from her eyes, and said, “And why is that?”

“It’s called, ‘respecting your elders.’ Ain’t you ever heard of it?”

“I guess so.”

“Mm-hmm,” Darlene said. “You can go in the bathroom and freshen up. There’s some clean washcloths in there, and some soap, and lotion, if you’re of a mind. Pour yourself a glass of water too.” She went back to her book.

Miriam did, and came back out in a few minutes, a dampened washcloth in her hand, wrapped around a glass of water.

“Feel better?”

“Yes, thank you, Miss Darlene.”

“You’re welcome.”

Miriam drank her water awhile, her eyes far away.

Darlene finished reading her chapter, and set the book aside.

The words fell in the silence like a stone tossed in the middle of a still lake:

“Comin’ home, ain’t you?”

Miriam went to take a sip of water, and couldn’t raise the glass.

“Yes,” she said, clearing her throat.

She tried to raise the glass again, and couldn’t; her breath hitched, and she tried again.

“You went to the city.” It wasn’t a question.

“Yes…” To her dismay, Miriam felt her face redden, and the tears came so fast and hard they stung. Her reflexes moved her hands to cover her eyes, and the glass fell from her hand as she began to break down.

The glass broke into shiny shards on the sunlit porch, the water spreading, filling the cracks and crevices as Miriam went on her knees.

“I’m sorry!” she cried, “Oh, oh, I’m so sorry!” Darlene knew she didn’t mean the glass.

Miriam bent over, her face in her hands, tears leaking through her fingers, her yellow hair limp and damp from the heat, hiding her face, draped over her shoulders; she could feel tiny splinters poking through her summer dress, and welcomed the pain.

Darlene rose from her chair, and made her slow way over to the young girl.

She raised Miriam off her knees, and held her.

“I know, child. I know.”

She swayed with Miriam in her arms as the girl cried.

“I didn’t mean it,” she said, her voice husky with sorrow.

“I know.”

“I didn’t know!”

“How could you know, being so young?”

“Oh, it hurts, Miss Darlene, it hurts so much!” Her body was trembling.

“Yes, baby, it’s gon hurt a lot, and maybe for a long time, but you gon be all right after awhile, Miriam. Time heals. God heals.”

Darlene held her until her sobs became sniffles. Miriam stepped out of the embrace, embarrassed somehow, before this woman, at what she was about to say.

She looked at the water drying on the porch floor.

“I don’t believe in God,” she said.

Darlene kept her hands on the girl’s shoulders, and gave a small smile.

“You don’t, huh? Then I guess you ain’t never heard of your namesake?”

“My…namesake?” She looked up.

“Miriam, the sister of Moses. You ain’t never heard?”

“No. We…we don’t go to church. My father…” she didn’t finish, and averted her eyes again.

“Well, sit down. I’ll be back.”

Miriam sat, wiping her eyes with the washcloth, which was also drying from the heat, but still wet enough for the task. She pulled her hair back off her neck, and tried to compose herself. Something was going on here, something strange and uncomfortable, but not frightening.

In the distance, three more hawks had joined the first. Miriam watched their silent, deadly circles.

And I was the mouse in the meadow.

She thought back to that moment she stepped off the bus, looking around in unadulterated wonder at the crowds, the buildings, the noise assaulting her ears, her senses flooded, and a smooth voice in her ear like a lifeline to someone drowning.

May I help you with your luggage, miss?

She looked away from the hawks.

Darlene came back, handed Miriam a new glass of water along with a fresh wet cloth, cold to the touch, and Miriam wiped her face and neck with it.

“Hang it on the railing with the other one. It’ll dry quick.”

“Okay.”

Darlene waited until Miriam had resettled herself.

“You ready to hear about Miriam?”

“My ‘namesake,’” she tried the word again, and gave a little smile. “I like that word.”

“Yes, she was. Bet your parents didn’t even know.”

“That would be a safe bet, Miss Darlene. I’m ready.”

*******************

Darlene told her of Miriam: how she had watched over Moses as he floated down the Nile and made sure he was safe, and how she led the women out of Egypt in a victory dance, singing songs of praise to God, and how she rebelled against Moses, and God struck her with a skin disease, and they had to put her outside the camp for seven days.

“And you know there ain’t no worse hell for a pretty woman than a skin disease,” Darlene said, laughing.

To her own surprise, Miriam started laughing too.

When the laughter subsided, Darlene continued.

“But you see, Miriam got jealous because God talked to Moses in a way he didn’t speak to her. She got jealous of what Moses had, and forgot that the only reason Moses had that close relationship was because he had a job God wanted him to do.

“See, Miriam had to wait in the same bondage with the rest of her people until her brother came back, and she was older than him. It wasn’t her job to lead the people out, but she did lead the women, ‘cause Moses couldn’t understand how that bondage was for them. Womenfolk’s pain is always different from men; it goes through us in places they don’t have, and I don’t mean what you might think. It goes deeper, and stays longer, and hurts more; you know that now, don’t you?”

“Yes, ma’am.”

“Ain’t no shame in knowin, child, and you found out young. Some women don’t find out til it’s way too late, and they lives is gone. Now this Miriam, she ain’t had no call to rise up against her brother, but y’see, people forget.

“She didn’t know Moses had to keep climbin’ mountains to speak to God, to keep on his knees to stop God from wipin’ the people out, cuz they was always complainin’. He had to work, to judge the people, to deal with their jealousy and pettiness.

“She was there, and she saw it all, but she didn’t know. All she saw was that God was talkin her brother in ways he didn’t talk to her, and it didn’t matter they was free, and on they way to a wonderful place.

“See, folks gets to lookin at what other folks have, and don’t know what they had to go through to get it, but they want it all the same.”

As Darlene spoke, a tear had pooled in the corner of Miriam’s lips, and she licked it off, tasting its bitterness. There had been harsh words and hard feelings at her departure. It all came down to one thing, the last thing she said before leaving: “I deserve better!”

Darlene let her words sink in as she looked at Miriam, who’d begun rocking the chair.

“You made the right choice to come back. Now, truth be told, girl, I don’t know why you got off that bus here, like you asked me earlier, but God knows. Now, you need to get on home, and let your heart and body heal from that beatin’ they done took.” “

“My family doesn’t know I’m here, Miss Darlene. I was afraid to tell them…”

“Honey, they know, and don’t you think they don’t. They didn’t know how long it would be. Soon’s they see you, they’ll know why you came back.”

“They may not be all that happy about it.”

“Well, my dealings with that side of town have not been good, but there’s only one way to find out, and it ain’t by staying here on this porch, now is it?”

“No,” Miriam said, looking at the broken glass.

“Well, I ‘spect they’ll be happier to see you than you think. Come here, girl.”

Miriam went to her, and knelt in front of her, and Darlene took Miriam’s face in her hands, lifting up her sea blue eyes to stare into the depths of her own rich brown ones; Miriam could see they were patient, kind, and full of life, lore, deep sadness and high joy, as her smooth pale cheeks were cupped in dark, calloused hands, like a warrior angel with a new-made chalice.

“You outside the camp now, Miriam, and you’re feeling diseased and wrong, but the only way you gon’ heal is by going back inside, among your own, and let them take care of you. Ain’t got no choice in the matter, no say-so. You spoke out against, and you went through your suffering days, and it’s time to get back. Whatever you do, from here on out, is gonna matter more not just to you, but to other folk, to your family, your husband, when you get one, your kids, when you have some. Your life is gonna be different now.

“You understand that?”

Miriam sighed, and shook her head, and rested it in Darlene’s lap awhile, as the old woman chuckled at the girl’s honesty, and stroked her hair, humming something low and sweet, and Miriam smiled. This was music.

After awhile, Darlene smiled and lifted her up as she got to her feet.

A cloud of dust was visible in the distance as the tires from the approaching bus rumbled over the road. The high sun lit it, fine and floating, a wind blown corona swirling in slow motion through the hot, still air.

“You wait here,” Darlene said, and went inside. She came back out with an old, yellow skinned tambourine, its shakers pitted with rust, its wood worn smooth and bright where hands gripped and slapped. There was a rotted piece of duct tape that was supposed to be a handle, and a smaller piece over a hole where her mother’s fingernail had pierced it.

She held it out to Miriam.

“This belonged to my mother,” said Darlene. “You take it.”

“Oh, Miss Darlene, I couldn’t!”

“Didn’t ask if you could, said I wanted you to take it. I want you to remind yourself of which Miriam you’re supposed to be. See, it’s just like you: it’s been beaten and shaken down to its core, but it’s still here. It got scars and hand marks, scrapes and patches, but it’s still here.”

She held the tambourine out again.

“So are you. You been through it, and now you need to lead others out.

“See, you think you comin’ home in defeat and shame, but you came out of that cesspool in victory, and now you know what to say to those young girls come after you gettin’ on that bus.”

Miriam opened her mouth to say something, but nothing came out. She closed it, her face flushing.

She tried again, but all that came out was, “I don’t know how to play it.”

Darlene laughed.

“Child, neither did Mama! Didn’t stop her none. The deacons had to take this from her she threw the choir off so bad; she’d start out all right, but after ‘while seemed like she just played to the rhythm in her heart, and it wasn’t what was going on up there at all. Happened every Sunday too, sure as sunrise, til she got too old to hold it anymore.

“Then, they just laid it there beside her, and she’d rest her hand on it.”

She wrapped Miriam’s fingers around the worn taped handle.

“Just before she passed on, she told me to keep it, ‘cuz she was gon get a new one when she got home. She don’ need it no more. I don’ either.”

Miriam smiled, and took the gift.

“Thank you.”

The bus pulled to a stop, the nimbus of dust bursting around it like a beggar’s halo.

“You’ll learn to play it in time, and when you’re ready to lead out, you’ll understand. Your time of bondage is over.”

Miriam looked at the worn and battered tambourine, then back at Darlene.

“Over,” she repeated, half in wonder, half in affirmation.

“God bless you, Miriam.”

She kissed Darlene’s wrinkled cheek. “He already has.”

As she crossed the dusty road, she tapped the ancient tambourine lightly against her knee, its rusty jingle breaking the afternoon stillness.

When the bus was gone, Darlene looked at the washcloths hanging like ephods on the old railing, and down at the broken glass, glinting in the sunlight, like the precious stones waiting to be placed on them.

It was a shrine to their time together, and Darlene smiled.

“You gon’ be just fine.”

© Alfred W. Smith Jr.

( May 16, 2014)